ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

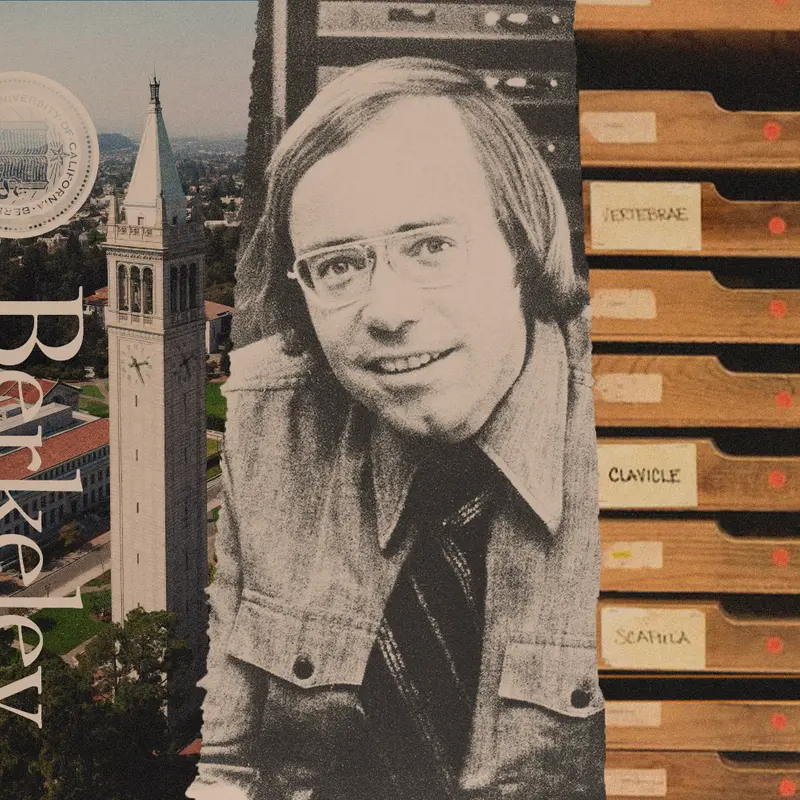

For decades, famed professor Tim White used a vast collection of human remains — bones sorted by body part and stored in wooden bins — to teach his anthropology students at the University of California, Berkeley.

White, a world-renowned expert on human evolution, said the collection was passed down through generations of anthropology professors before he started teaching with it in the late 1970s. It came with no records, he said. Most were not labeled at all or said only “lab.”

But that simple description masked a dark history, UC Berkeley administrators recently acknowledged. UC Berkeley conducted an analysis of the collection after White reported its contents in response to a university systemwide order in 2020 to search for human remains. Administrators disclosed to state officials in May that the analysis found the collection includes the remains of at least 95 people excavated from gravesites — many of them likely Native Americans from California, according to previously unreported documents obtained by ProPublica and NBC News.

The university’s disclosure was particularly painful because it involved a professor who many Indigenous people already viewed as a primary antagonist, according to interviews with tribal members.

UC Berkeley has long angered tribal nations with its handling of thousands of ancestral remains amassed during the university’s centurylong campaign of excavating Indigenous burial grounds.

More than three decades ago, Congress ordered museums, universities and government agencies that receive federal funding to publicly report any human remains in their collections that they believed to be Native American and then return them to tribal nations.

UC Berkeley has been slow to do so. The university estimates that it still holds the remains of 9,000 Indigenous people in the campus’ Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology — more than any other U.S. institution bound by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, according to a ProPublica analysis of federal data.

That tally does not include the remains that White reported and relinquished in 2020. For decades, White served as an expert adviser in the university’s repatriation decisions, sitting on committees that weighed whether to grant or deny tribes’ requests, according to a review of hundreds of pages of federal testimony and internal university documents.

White said the collection did not need to be reported under NAGPRA because there is no way to determine the origin of the bones — and therefore the law does not apply.

The collection has exposed deep rifts at UC Berkeley, pitting a prominent professor who said he’s done nothing wrong against university administrators who have apologized to tribes for not sharing information about the remains sooner.

For tribes the episode follows a familiar pattern of UC Berkeley’s delays and failures to be transparent with them.

“This is a major moral, ethical and potentially legal violation,” said Laura Miranda, a member of the Pechanga Band of Indians and chair of the California Native American Heritage Commission. She made her comments at a July hearing held by the commission, which oversees the university system’s handling of Indigenous remains.

UC Berkeley officials declined interview requests, saying “tribes have asked us not to.” In a statement, the university said White was no longer involved in repatriation decisions. There is now a moratorium on using ancestral remains for teaching or research purposes, according to the statement. The Hearst Museum is currently closed to the public so that staff can prioritize repatriation.

The university also acknowledged that, in the past, UC Berkeley had “mishandled its repatriation responsibilities.”

“The campus privileged some kinds of scientific and scholarly evidence over tribal interests and evidence provided by tribes,” the university said in the statement.

In an interview with ProPublica and NBC News, White said he’s been villainized for strictly adhering to the federal law, which he said requires balancing scientific proof with other evidence.

In the years immediately after Congress passed NAGPRA, UC Berkeley relied on White’s expertise as curator of the museum’s skeletal collection to challenge Indigenous people’s repatriation requests, according to testimony before a federal advisory committee.

Some tribal members accused him of demanding too high a burden of scientific proof for repatriations and discounting knowledge passed down through the generations. In the 1990s, he made headlines for fighting to use Native American remains as teaching tools, arguing that students should not be deprived of the opportunity to learn from them. He later sued to block the UC system from returning two sets of remains estimated to date from 9,000 years ago.

NAGPRA does not require definitive scientific proof for repatriation, only that institutions report human remains that could potentially be Native American and consult with the affected tribal nations, said Sherry Hutt, an attorney who is a former program manager of the federal National NAGPRA Program. “It’s not a scientific standard. It’s a legal standard,” she said.

White often had the backing of university administrators in disputes over remains, but not anymore. At the July hearing before the California Native American Heritage Commission, UC Berkeley administrators cited an analysis by another anthropologist at the school, Sabrina Agarwal, that determined thousands of the bones in the collection were excavated from gravesites.

Given UC Berkeley’s legacy of raiding Native American graves, it is likely the collection White taught with contains the remains of Native Americans from what is currently California, said Linda Rugg, associate vice chancellor for research at the university.

“I want to apologize for the pain that we caused by holding on to this collection,” Rugg said at the hearing. “When we found out about it, we were dismayed ourselves.” A university spokesperson said staff and administrators are consulting with several tribes on next steps. Federal officials confirmed UC Berkeley has contacted them requesting guidance.

White, who retired last spring but is still a professor emeritus, said administrators knew about the collection, which was used to teach hundreds of students over the years. “It is very disappointing to find the Berkeley employees are making false allegations and misrepresentations,” he said.

Behind UC Berkeley’s reckoning is the centurylong saga about a powerful, progressive institution that is finally confronting its past. Isaac Bojorquez, chairman of the KaKoon Ta Ruk Band of Ohlone-Costanoan Indians of the Big Sur Rancheria, called for accountability for the newly reported remains, but also for UC Berkeley’s decadeslong delays and denials of other tribes’ repatriation requests.

“We want our ancestors,” he said. “They should have never been disturbed in the first place.”

A Painful History

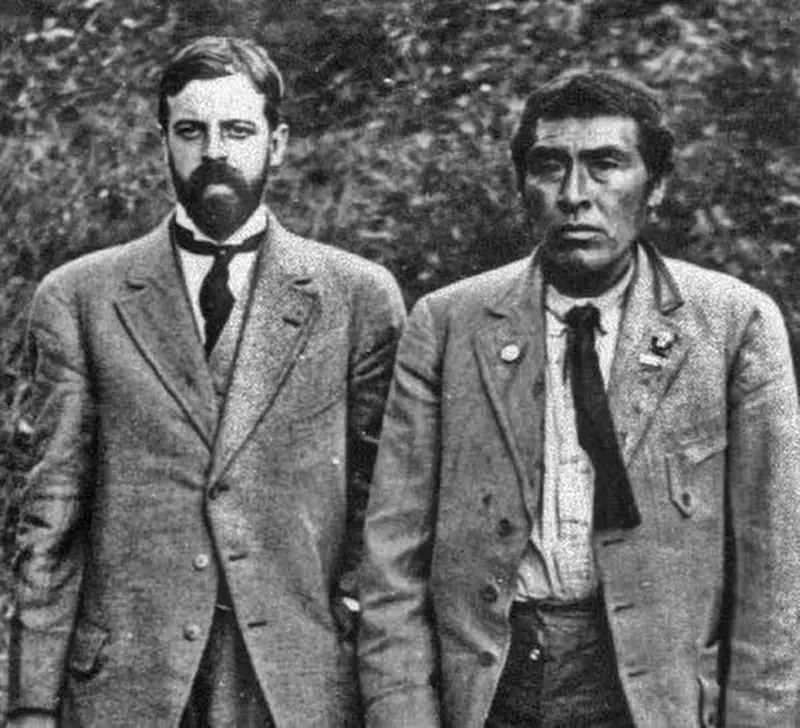

With no documentation for the origin of his teaching collection, White surmised in a report to university officials in 2020 that it dated back to UC Berkeley’s early days and the university’s first anthropology professor, Alfred Louis Kroeber.

Kroeber, who joined the faculty in 1901, became a world-renowned scholar for his research on Native Americans in California, encouraging the excavations of Indigenous gravesites during his four-decade tenure.

His name recently was stripped from Berkeley’s anthropology building, in part for housing an Indigenous man found in the Sierra Foothills as a living exhibit at what would later become the Hearst Museum. Described as the last living member of his band of Yahi Indians, the man — whom Kroeber called “Ishi” — was studied and made to craft arrows and greet visitors for nearly five years, until his death in 1916.

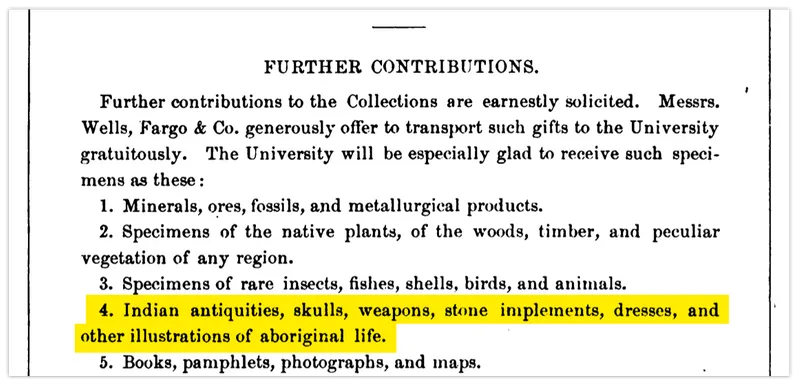

The Hearst Museum continued for decades to voraciously collect Native American remains and funerary objects, trying to assemble a collection to rival the British Museum and Harvard University, said historian Tony Platt, a distinguished affiliated scholar at UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law and Society. “To be a great university you’ve got to acquire stuff, you’ve got to hoard massive amounts of things,” Platt said.

The vast majority of UC Berkeley’s collection of remains came from sacred ancestral sites in California, according to ProPublica’s analysis of federal data. The collection included ancestors of the Ohlone, the tribe whose land was seized by the federal government to fund public universities, including UC Berkeley.

The university eventually amassed the remains of about 11,600 Native Americans, stored in the basement beneath its gymnasium swimming pool and in other campus buildings. But Platt said that number is likely an undercount because museum records often counted multiple remains excavated from the same gravesite as one person.

In the early 1970s, Native American activists’ long-standing resistance to the grave robbing started gaining momentum amid protests that stealing from Native Americans’ burial sites in the name of science was a human rights violation.

By then, the teaching collection that anthropology professors used had grown to thousands of bones and teeth that White said in his report to university administrators had been commingled with others donated by amateur gravediggers, dentists, anatomists, physicians, law enforcement and biological supply companies.

The remains were unceremoniously sorted by body part so students could study them. A jumble of teeth. A drawer of clavicles. Separate bins for skulls. For decades, anthropologists added to the collection, used it in their classes and then passed it along to the professors who came after them, White said.

It was this collection that White started teaching with when he joined UC Berkeley’s anthropology faculty in 1977.

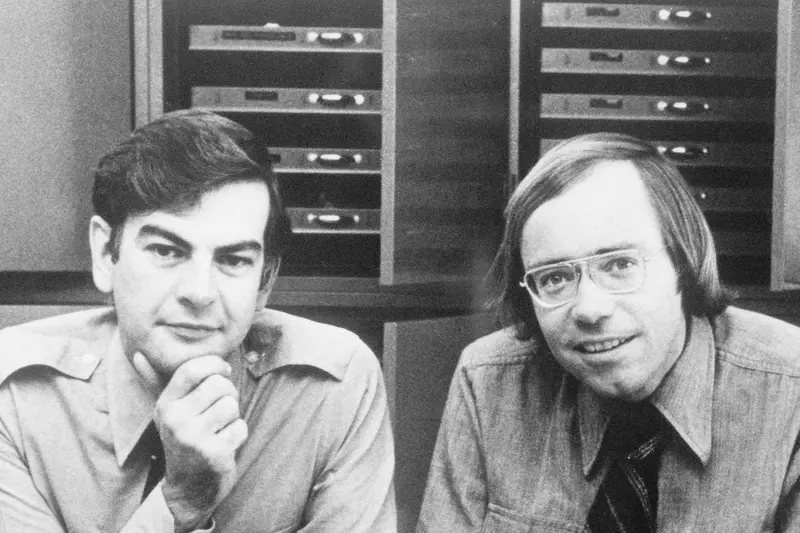

UC Berkeley hired White, then 27, soon after he had obtained his Ph.D. in biological anthropology from the University of Michigan. He already was collaborating with a team to analyze “Lucy,” a 3.2-million-year-old human ancestor.

White published articles in prestigious journals and co-authored a textbook, “Human Osteology,” that boasted of UC Berkeley’s collection of human remains and called ancient skeletons “ambassadors from the past.”

Congress passed NAGPRA in 1990, recognizing that human remains of any ancestry “must at all times be treated with dignity and respect.” As UC Berkeley prepared to comply with the new law, the campus museum appointed White curator of biological anthropology, overseeing the university’s collection of human remains.

Almost as soon as tribes started making claims to ancestral remains under NAGPRA, Indigenous people accused White of undermining their efforts to rebury their ancestors, according to a review of hundreds of pages of testimony before a federal review committee tasked with mediating NAGPRA disputes.

Since NAGPRA only applied to federally recognized tribal nations, many tribes in California were not entitled to seek repatriation. (Of the 183 tribes in the state, 68 still lack federal recognition, according to the Native American Heritage Commission.) UC Berkeley’s collection of remains included those of thousands of people designated as unavailable for repatriation because they came from tribes lacking federal recognition.

Recourse under the law was limited, leaving tribal nations to file formal challenges with the federal NAGPRA Review Committee, an advisory group whose members represent tribal, scientific and museum organizations. It can only offer recommendations in response to disputes.

In the first challenge following the passage of the law, in February 1993 the Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna O Hawai’i Nei, a Native Hawaiian organization, took a dispute over repatriation of two ancestral remains before the federal committee. The remains had been donated to UC Berkeley in 1935, at which time a museum curator classified them as Polynesian. White disagreed.

Addressing the committee, White introduced himself as “the individual who is responsible for the skeletal collections at Berkeley.” He argued the remains might not be Native Hawaiian and could belong to victims of shipwrecks, drownings or crimes. They should be preserved for study, he added, making an analogy to UC Berkeley’s library book collection, where historians access volumes for years as their understanding evolves.

Edward Halealoha Ayau, then the Native Hawaiian organization’s executive director, pounded his fists on the table in outrage. “We do not have cultural sensitivity to books. We did not descend from books,” he said, according to a transcript of the meeting.

Ancestral remains are not research material, Ayau said, they are people with whom he shares a connection — a perspective that is central to Native Hawaiian culture.

White recently said that his analogy comparing human remains to books was taken out of context. “Both hold information,” he said. “I was obviously speaking metaphorically.”

Instead of recommending that both ancestors’ remains be repatriated directly to the Hui Mālama, the committee advised UC Berkeley to return one of them and send the other to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu for analysis, Ayau said. There, researchers finally agreed that the remains were Native Hawaiian — but only after conducting a scientific analysis over Ayau’s objections.

“I just started crying,” Ayau, who now chairs the federal NAGPRA Review Committee, recalled in a recent interview. “We failed to prevent one more form of desecration.”

The Bishop Museum declined to comment on its role in the 1993 repatriation, saying it happened too long ago for anyone to have knowledge of it.

For Ayau, the experience left him with a sense of loss over the treatment of his ancestors.

“To have someone disturb them is really bad,” he said. “But then to have them steal them and then fight you to get them back is beyond horrific.”

“Berkeley Should Be Ashamed”

White’s fight to use a set of Native American remains he had borrowed from the Hearst Museum for teaching purposes made headlines in the 1990s after he clashed with then-museum director Rosemary Joyce. She said when she was hired in 1994, it was common practice for White and other museum curators with keys to borrow ancestral remains and belongings without documenting what they’d taken.

“Just leaving aside NAGPRA, as a museum anthropologist, that’s an unacceptable thing,” she told ProPublica and NBC News. “When materials are not in the physical control of the staff of the museum, you need legal documentation.”

She changed the locks on the museum’s storage space. Heeding requests from tribes, she tried to recall a museum collection of Native American remains that White kept on loan in his lab and used for teaching. White refused to return them.

The vice provost for research of the UC system sent Jay Stowsky, then the system’s director of research policy, to mediate the dispute between White and Joyce. Stowsky agreed with Joyce, calling the lack of controls at the museum “terrible.” He said human remains were “just sort of thrown into boxes” with a label on them. “Berkeley should be ashamed of itself on so many levels,” Stowsky, now a senior academic administrator at UC Berkeley, said in a recent interview.

White filed a whistleblower complaint with the university in 1997 accusing the museum, under Joyce’s leadership, of seeking an unnecessary extension to NAGPRA’s reporting deadline. (Campus investigators found no improper activity, according to White.)

Joyce said she was simply trying to account for all the remains that would need to be reported under NAGPRA. “It’s really kind of insane to have to say, I did the thing that the law said I should do,” she told ProPublica and NBC News. Joyce said the complaints were found to be “meritless.”

White then filed an internal grievance against Joyce with the school’s Academic Senate, alleging that by asking him to relinquish the human remains she had infringed on his “academic privileges.”

The university brokered a deal: White could keep ancestral remains provided museum staff and tribes could access them to conduct inventory and report them under NAGPRA.

Joyce said the arrangement was untenable and she felt unsupported by the university’s leadership. White continued to teach with the remains.

A Decade After NAGPRA

Myra Masiel-Zamora, now an archaeologist for the Pechanga Band of Indians, enrolled in White’s osteology class more than 20 years ago when she was 18 and a first-year student. But, she said, she withdrew from the course after a teaching assistant told her the human remains belonged to Native Americans.

“That was the first time I really truly learned that an institution could and can — and is — using real Native American ancestors as teaching tools,” she said. “I was really upset.”

Concern over institutions’ handling of Indigenous remains extended beyond the classroom.

Troubled by the slow pace of repatriations under NAGPRA, California lawmakers passed their own version of the law in 2001, aiming to close loopholes in the federal statute and allow tribes to claim remains regardless of whether they have federal recognition. But the state failed to fund an oversight committee established by the bill.

In 2007, without consulting tribes or offering public explanation, UC Berkeley abruptly fired museum employees who were responsible for NAGPRA compliance, and named White and others to a newly formed campus repatriation committee, according to tribal leaders.

That upset tribal members, who brought their concerns about the new committee to state senators. The firings “eliminated the only staff at the university that would stand up to Mr. Tim White and his offensive remarks regarding Native American tribes and our ancestral remains,” Reno Franklin, then a council member and now the chairman of the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians, said during a 2008 state legislative hearing.

In emails sent to ProPublica and NBC News, White sought to discredit the testimony by Franklin and others at the hearing by saying that it had been the result of a decadeslong effort by the university to use him as a scapegoat for its failures. White said he only held an advisory role and did not make final repatriation decisions.

Meanwhile, White’s career was skyrocketing after he co-led a team that discovered and excavated a 4.4-million-year-old hominid unearthed in Ethiopia. It was deemed the scientific breakthrough of the year in 2009 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science and cemented his reputation in the field. It also landed him, along with the likes of Barack Obama and Steve Jobs, on Time magazine’s 2010 list of the world’s 100 most influential people.

Two years later, White and two other professors sued to block the repatriation of two 9,000-year-old skeletons to the Kumeyaay, 12 tribes whose homelands straddle the U.S.-Mexico border near San Diego. White and the other professors wanted to study the remains, which had been unearthed in 1976 from the grounds of the chancellor’s house on the University of California, San Diego, campus.

They argued that there wasn’t enough evidence to support the Kumeyaay’s ancestral connection to the remains, and that the UC system had failed to prove that the remains could legally be considered “Native American.” Based on the professors’ interpretation of the law, human remains had to have a cultural or biological link to a present-day tribe to be considered Native American.

They said that not allowing them to study the remains violated their rights as researchers. An appeals court ruled against the professors, citing the Kumeyaay’s sovereign immunity, meaning they couldn’t be sued.

As tribes’ frustration with the lack of progress on repatriations grew, UC Berkeley convened a “tribal forum” in 2017. In the private gathering, tribal leaders and others expressed anger that university staff, including White, had resisted their requests to repatriate and that the university was requiring an excessive amount of proof to reclaim ancestors, according to an internal university report.

The following year, UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ disbanded the campus’ NAGPRA committee that White had served on, records show. The university established a new one that did not include him.

Meanwhile, Berkeley prepared for its biggest repatriation to date: the return of more than 1,400 ancestors to the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, a small tribe whose ancestors’ remains were excavated from burial grounds along California’s coast and Channel Islands. According to the school’s NAGPRA inventory records, many of the remains had been taken by an archaeologist in 1901 whose expeditions were funded by Phoebe Apperson Hearst, wife of mining magnate George Hearst and namesake of UC Berkeley’s anthropology museum.

UC Berkeley held on to the Chumash remains and loaned some to White for research projects, before returning them to the tribe in the summer of 2018.

When the repatriation day finally came, Nakia Zavalla and other tribal members drove 300 miles to campus and entered a backroom of the anthropology building where UC Berkeley stored their ancestors.

“Going into that facility for the first time was horrifying. Literally shelves of human remains,” said Zavalla, the tribe’s cultural director. “And you pull them out, and there’s ancestors mixed all together, sometimes just all femur bones, a tray full of skulls.”

Zavalla said tribal members had to bring their own cardboard boxes to carry their ancestors home for burial — a complaint other tribal nations have made in dealing with the university. UC Berkeley officials said they were unaware of Zavalla’s “disturbing account” but have changed their policies to ensure they provide assistance “as requested by Tribes.”

Zavalla said the visit highlighted how the university had deprived the tribe of more than ancestral remains, she said. The university housed recordings and items that ethnographers and anthropologists had previously collected from Chumash elders.

For Zavalla, the information could have benefited her and other tribal members’ efforts to revitalize the Santa Ynez Chumash’s language and traditions — which government policies once sought to eradicate. But the information was not freely shared, she said: “They stole those items.”

“They Need to Go Home”

California state lawmakers passed a bill in 2018 to expand the Native American Heritage Commission’s oversight of repatriation policies and compliance committees within the UC system. The legislation called for an audit of all UC campuses’ compliance with NAGPRA.

The following year, UC Berkeley finally barred the use of Native American remains for teaching or research, according to the university.

The state auditor’s office announced the results of its review in 2020, singling out UC Berkeley for making onerous demands of tribes claiming remains.

The auditor also noted that UC Berkeley had identified 180 missing artifacts or human remains. In a statement, UC Berkeley said staff had searched for the missing remains and artifacts, some of which had been lost for more than a century.

Soon after the audit, the UC president’s office called for all campuses to search departments that historically studied human remains for any that had not been previously reported.

In August 2020, White reported the contents of the collection he taught with to university administrators.

White told ProPublica and NBC News that given the lack of documentation, it would be impossible to determine if they were Native American, much less say which tribe they should be returned to.

“There’s nobody on this planet who can sit down and tell you what the cultural affiliation of this lower jaw is, or that lower jaw is. Nobody can do that,” he said.

The Native American Heritage Commission is continuing to press UC Berkeley for answers and accountability for its handling of the collection White reported.

Bojorquez, the tribal chairman and an NAHC commissioner, said it was “mind-blowing” that Berkeley still has not provided any documentation on the origins of the collection.

The university should have consulted tribes sooner, he said, to ensure the remains were handled respectfully and to help speed the repatriation process. “So much happened to these ancestors,” he said — they should not be in a box or on a shelf.

“They need to go home,” he said.

More Missing

Separate from the teaching collection that White reported in 2020, he also notified administrators that he’d discovered remains with museum labels stashed in gray bins in a teaching laboratory. They later were identified as the partial remains of six ancestors of the Santa Ynez Chumash that were supposed to have been repatriated in 2018.

When UC Berkeley finally informed the Chumash six months later, it felt like a “blow to the chest,” said Zavalla, the tribe’s cultural director. Zavalla and other tribal staff members drove to Berkeley to retrieve the remains.

“I felt lied to,” she said. “They did not give us all of the ancestors, and they didn’t do their due diligence.”

The discovery of the missing remains outraged Sam Cohen, an attorney for the tribe, who called for probes into whether UC Berkeley or White had violated policies or laws.

“He is considered untouchable, I think, by Berkeley because he’s so famous in human evolution,” Cohen said of White. “He basically wasn’t going to voluntarily comply with anything until he was forced.”

White said he was unsure how the remains ended up in the teaching laboratory. He suggested they may have been mistakenly placed in his lab during a move years ago while he was overseas. He provided ProPublica and NBC News with a copy of an email from an investigator with UC Berkeley's Office of Risk and Compliance Services, which said the office found no violation on his part regarding the Chumash remains. UC Berkeley declined to comment on the outcome of the investigation, calling it a personnel matter.

“I have accounted for everything that happened in granular detail,” White said in an interview.

Chancellor Christ apologized to the tribe in December in a letter and acknowledged: “We do understand that, given our history, it is difficult for tribes to have confidence in our university and Professor White.”

The apology was little consolation, Cohen said, especially since it came with yet another painful acknowledgement. University records show there are still more unreturned Chumash ancestors. So far, they have yet to be found.

Christ assured the Chumash that the university was committed to returning all Native American ancestors to all tribes. UC Berkeley officials estimate it will be at least a decade before that happens.

March 5, 2023: A photo caption with this story originally misstated the positions of Kalehua Caceres and Edward Halealoha Ayau. Caceres was representing the Office of Hawaiian Affairs but is not an employee. Ayau is the former director of Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna O Hawai’i Nei, not its current executive director.

March 16, 2023: This story originally incorrectly described Tim White’s argument in a lawsuit seeking to block a repatriation of human remains to the Kumeyaay tribes. The lawsuit argued that there wasn’t enough evidence to support their ancestral connection to the remains and that the UC system had failed to prove that the remains could legally be considered “Native American.” It did not argue that the remains were too old to be linked to any living descendants.

Alex Mierjeski contributed research. Ash Ngu contributed data analysis.

Clarification, March 16, 2023: This article was updated after publication to more fully describe Tim White’s role in the discovery and excavation of the fossil Ardi. He co-led the international team.