This article is co-published with The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages with Texans, and with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for newsletters from The Texas Tribune and The Marshall Project.

In October 2005, Texas Gov. Rick Perry traveled to the border city of Laredo and announced Operation Linebacker, a new initiative that he said would protect the state’s residents from terrorist groups such as al-Qaida.

Without pointing to evidence, Perry said such terrorist groups, along with drug cartels and gangs, were attempting to exploit the U.S.-Mexico border. A press release from the governor’s office said Perry warned that after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, criminal organizations could “import terror, illegal narcotics and weapons of mass destruction.”

Perry said Texas would step in to fill the gaps left by the federal government, increasing state law enforcement presence along the border and providing new investigative tools. He stopped short of directly attacking President George W. Bush or the Republican-led Congress. “The state of Texas cannot wait for the federal government to implement needed border security measures,” Perry said, explaining that the state would use $10 million in funding that included federal grants for the operation. Two months later, the governor highlighted his border security efforts while announcing his reelection campaign.

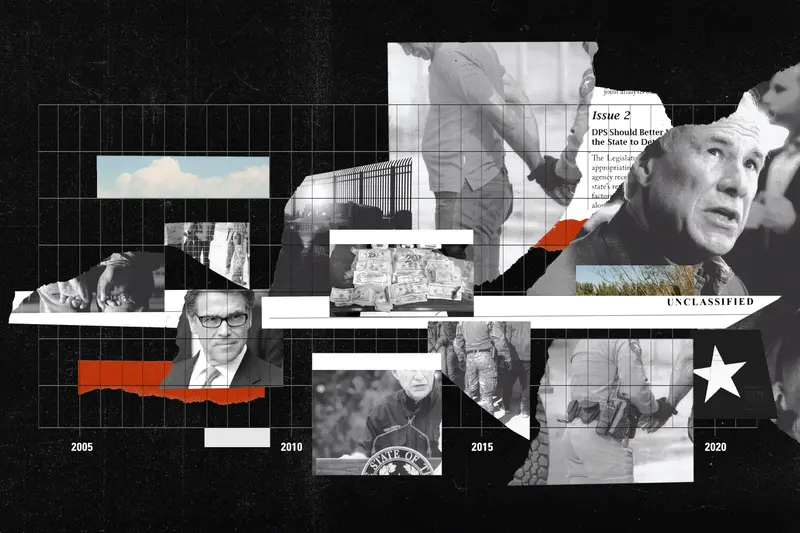

Over the next 17 years, Perry and his successor, Gov. Greg Abbott, persuaded the Texas Legislature to spend billions of dollars on border security measures that included at least nine operations and several smaller initiatives. Each time, the governors promised that the state would do what the federal government had failed to: secure the border.

The pronouncements often coincided with their gubernatorial campaigns or times when they were considering bids for higher office. Perry and Abbott also ramped up their political attacks on the federal government during periods when Democrats held the presidency or a majority in Congress.

In 2007, with Bush still in office but Democrats in control of Congress, Texas allocated $110 million in state funding to border security. The figure swelled to nearly $3 billion last year as Abbott criticized newly inaugurated President Joe Biden, claiming Biden had not done enough to stop drug and human smuggling.

In launching Operation Lone Star in March 2021, Abbott claimed the initiative would “combat the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas.” About four months later, the governor also directed state police and the National Guard to arrest some immigrant men on criminal trespassing charges for crossing the border through private property.

Abbott, who is seeking reelection, expanded the operation in the past two weeks. He directed the Texas Department of Public Safety to inspect every commercial truck crossing into the U.S. through the state, a move that has drawn criticism for hampering border commerce. Abbott discontinued the inspections days later, saying he’d reached agreements with his Mexican counterparts to increase enforcement south of the border. Some of the security measures included in the agreements had already been in place in Mexico.

The governor also started busing immigrants, who are processed and released by the federal government, to Washington, D.C., on a voluntary basis. Abbott said both measures were in response to the Biden administration’s decision to bring an end, in May, to Title 42, a pandemic-era emergency health order under which most immigrants, including those seeking asylum, could be immediately turned away from the border.

An investigation by ProPublica, The Texas Tribune and The Marshall Project last month revealed that the numbers the state reported to demonstrate Operation Lone Star’s success have included arrests that had nothing to do with the border or immigration and drug seizures from across the state made by troopers stationed in targeted counties prior to the operation.

The way the governors and their administrations have tracked success has fluctuated over the years, offering little clarity into whether the state is closer to securing the border today than it was nearly 20 years ago.

Neither the governor’s office nor the DPS, the main agency leading border security efforts, can provide a full breakdown of the state-led operations since 2005, their duration, their cost to taxpayers and their accomplishments. Because the state has declined to provide such information, the news organizations compiled a partial list of recent border operations and their outcomes using news releases and media coverage, as well as reports by both the Texas Legislative Budget Board, the state’s top budget analysts, and advocacy groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union.

Perry could not be reached for comment through a representative. Abbott’s office didn’t respond to questions about tracking the success of the state’s initiatives and the continued need for border operations. Instead, Abbott spokesperson Renae Eze repeated the governor’s claims that the latest operation was a response to the federal government’s failure under Biden to secure the border. She reiterated that Operation Lone Star kept “millions of deadly drugs and thousands of criminals and weapons” off the streets.

2005

Operation Linebacker

Description: Launched to reduce border crime and violence, the operation was led by the Texas Border Sheriff’s Coalition, which represents law enforcement agencies across the region. The initiative allocated federal criminal justice grants through the governor’s office to local law enforcement for patrols in “high threat” areas. It sent at least 200 DPS troopers to the border temporarily, permanently assigned 54 DPS investigators to the region and deployed National Guard members to provide training for local law enforcement, according to the Associated Press reports and press releases from the governor’s office.

Stated reason: Perry pointed to the 9/11 attacks as justification for the operation. “Al Qaeda and other terrorists and criminal organizations view the porous Texas-Mexico border as an opportunity,” he said in a statement. The governor praised the federal government for providing 1,000 new Border Patrol agents and making other investments, but said the Republican-led Congress needed to do more.

End date: 2006

Cost: Roughly $10 million in federal criminal justice grants distributed through the governor’s office.

Claimed success: The initiative seized more than $3 million in cash, along with drugs worth more than $77 million and weapons valued at more than $36,200, according to a 2015 Legislative Budget Board report. The state’s budget analysts also noted a lack of consistent reporting on border security that they said made it difficult to determine whether funding was appropriately allocated or if the expected outcomes were achieved.

Reported concerns: A November 2006 analysis from the El Paso Times found that 16 participating sheriff’s departments spent federal dollars, intended to fight drugs and crime, to instead enforce immigration laws. Officers caught undocumented immigrants seven times more often than they arrested criminals, according to the newspaper. The El Paso Times also obtained state reports from the operation that did not show any terrorism-related arrests over a six-month period.

2006

Operation Rio Grande

Description: The operation aimed to “attack ruthless, transnational criminal enterprises and gangs,” Perry said in a press release. The initiative, which the governor launched in February, became the umbrella operation for several smaller measures. (Perry’s office counted the narrower initiatives as individual operations). Those measures deployed additional resources, including National Guard members, for approximately three-week periods to border regions including El Paso, Laredo and Del Rio.

Stated reason: Perry pointed to several incidents that had taken place in Mexico, including the arrest of four Iraqi men reportedly headed to the U.S., to justify the need for the operation. “There is not only great concern that the drug trade is becoming more aggressive, but that terrorist organizations are seeking to exploit our porous border,” Perry said at the time. “The state will not wait for Washington to take all the necessary actions.” The governor did not mention Bush or the Republican-led Congress.

End date: October 2006

Cost: Unclear. A spokesperson for Perry told The Brownsville Herald that as part of Operation Rio Grande, Texas sent nearly $25 million to local law enforcement agencies between October 2005 and September 2006, but the article did not specify how much was spent on individual operations. The funding was a combination of state and federal dollars.

Claimed success: On Oct. 17, 2006, Perry touted a crime reduction of about 60% in participating border counties. The El Paso Times reported that Steven McCraw, who at the time was the Texas Homeland Security director, acknowledged the figure did not prove there had been a sustained drop in crime or reflect issues such as criminals shifting their activities to another area. Instead, it represented the average decrease compared to the previous year in several counties where law enforcement “surges” had been carried out at varying times over a four-month period.

Reported concerns: Experts told the newspaper that Perry and state officials failed to account for other reasons that crime could fall before and after the operations or what types of crimes had declined. A Border Patrol spokesperson also told the newspaper that illegal border crossings had dropped dramatically before the state-led operations began.

2007

Operation Wrangler

Description: Launched in January, the initiative included the work of more than 6,800 local, state and federal law enforcement personnel. They focused on known “smuggling corridors” along the border and in areas hundreds of miles away such as Dallas. The operation deployed vehicle, marine and air support to the border.

Stated reason: Perry recognized Mexico’s newly elected President Felipe Calderón for cracking down on drug cartels, but cited continued violence in that country as a reason for ramping up border security funding. He said the operation was needed to “send a message to drug traffickers, human smugglers and criminal operatives that their efforts to exploit our international border will come at a great cost to them and their illegal operations.”

End date: July 2007

Cost: Unclear. A 12-day National Guard deployment under the operation cost $1.1 million, according to the Legislative Budget Board.

Claimed success: Perry said the initiative arrested “hundreds of criminals” and seized “thousands of pounds of illegal drugs” during the first “high intensity phase” that ran from Jan. 17 to Jan. 29. More than 2,770 people were sent to federal immigration officials for deportation and 136 people were detained on human smuggling charges during that period, according to the release. That April, Perry claimed another phase of the initiative had reduced crime by 30% in the El Paso area during a 30-day period. A review of news reports by ProPublica, the Tribune and The Marshall Project was unable to find evidence that the governor provided data to substantiate those claims.

Reported concerns: After about a week, the Mexican Consulate in Dallas raised concerns about racial profiling to the Dallas Morning News. A consulate spokesperson said dozens of people were stopped for traffic violations and illegally asked for their immigration documents. The spokesperson pointed out state and local officials were not authorized to enforce federal immigration law. In response to the allegations, a spokesperson for Perry’s office told the news organization that while the operation didn’t target immigrants, law enforcement officers were within their rights to call in immigration officials if they discovered people were in the state without authorization.

Operation Border Star

Description: The initiative focused on reducing crime in targeted regions along the border by deploying local and state resources, including an undisclosed number of National Guard members, to coordinate with Border Patrol. The San Antonio Express-News reported in 2012 that the initiative provided money to law enforcement agencies along the Rio Grande for border-related expenses and aided information-sharing between federal, state and local law enforcement agencies.

Stated reason: Without providing proof, Perry claimed Mexican cartels were using gangs, like the Salvadoran group MS-13, to support their operations by “torturing, kidnapping and murdering citizens on both sides of the border.” Perry’s office wrote in a 2008 editorial that more than 430 people with “terrorist ties” had been arrested after crossing into Texas illegally since March 2006. A 2021 report by the Cato Institute, a libertarian organization in Washington, D.C., found that between 1975 and 2020, just nine people who were later convicted of planning a terrorist attack had entered the country illegally. Three of them came across the southern border, according to the report.

End date: Ongoing. The Legislative Budget Board wrote in a 2015 report that all border operations since October 2007 had been folded into Border Star.

Cost: Unclear. In 2007, the Legislature budgeted $110 million in state funding for border security. The allocation included money for Border Star, but it is not clear how much was specifically intended for that operation. The governor’s office awarded at least $43 million to local jurisdictions from 2008 through 2017 as part of Operation Border Star, according to records released to ProPublica, the Tribune and The Marshall Project.

Claimed success: Less than a month after the operation’s launch, Perry’s office claimed in a press release that the initiative had seized more than 11,000 pounds of marijuana, 35 pounds of cocaine and 7 pounds of methamphetamine. The governor also attributed the arrest of 170 unauthorized immigrants in that period to the initiative. Perry’s office claimed that a reduction in calls for assistance to local law enforcement reflected a decrease in criminal activity. The news organizations did not find media stories or reports examining his claims of decreases in criminal activity.

Reported concerns: The operation led to a high level of traffic enforcement, but few substantial drug seizures, according to an ACLU analysis of performance measures for 11 local law enforcement agencies. “Given that traffic stops do not yield effective results for combating organized crime, law enforcement would make better use of resources by investigating serious crimes,” the ACLU concluded in the report.

2012

Operation Drawbridge

Description: A program led by DPS, border sheriffs and Border Patrol that began by installing and monitoring 500 low-cost motion-detecting cameras on participating farms and ranches near the Texas-Mexico border. (The number of cameras has since grown to about 5,500.) As part of the operation, information is shared with federal, state and local law enforcement, who can respond when the cameras are triggered. The operation’s start date is unclear, but a news release by DPS stated that the initiative had had a sustained impact on human and drug smuggling since January 2012.

Stated reason: In announcing additional funding for the operation in October 2012, Texas Agriculture Commissioner Todd Staples said the cameras were needed to protect landowners harmed by drug and human trafficking.

End date: Ongoing

Cost: Unclear. In 2016, DPS pointed to $4.8 million in expenditures since 2012 after installing about 3,300 cameras. In 2021, the Legislature provided an additional $10 million for the cameras, according to state financial reports.

Claimed success: DPS said in an April 2015 news release that the operation apprehended more than 56,200 people and seized more than 112 tons of drugs. The agency didn’t include proof of those claims.

Reported concerns: State Sen. César Blanco, an El Paso Democrat who was a state representative at the time, was among those who questioned the state’s role in enforcing immigration and the security of the camera system. The operation was a continuation of a 2008 camera program that made only 26 arrests over four years at a cost of roughly $153,800 per arrest, according to the El Paso Times.

2013

Operation Strong Safety

Description: The operation consisted of a three-week deployment of DPS troopers, Texas military personnel and other state law enforcement to the Rio Grande Valley, according to DPS officials. The initiative focused on “conducting around-the-clock saturation patrols on, above and along the Rio Grande River to detect and interdict a substantial percentage of drug and human smuggling activity.” It also included roadside DPS checkpoints.

Stated reason: In a news release, DPS said the operation was launched to address “significant criminal activity,” a “significant number of commercial vehicles on the roadways” and “unsafe driving practices.” The agency tied the three target issues to cartels, saying “increases in Mexican cartel smuggling activity decreases the safety and security of the Rio Grande Valley.”

End date: Oct. 4, 2013

Cost: Unclear.

Claimed success: DPS reported to the state’s budget board that drug seizures in the Rio Grande Valley dropped when the operation was active, from Sept. 15 to Oct. 4, 2013, an indicator that state officials have at times presented as proof of success. The agency compared the three weeks of the operation to the previous three-week period and found a decrease of 49% in marijuana seizures, 42% in cocaine seizures and 95% in methamphetamine seizures, according to news reports.

Reported concerns: State Rep. Terry Canales, a Democrat from the Rio Grande Valley, was among several lawmakers who questioned McCraw in 2013 about the legality, cost and geographic scope of the initiative. Canales said his office had received about 100 calls that claimed DPS checkpoints targeted poor neighborhoods and immigrant communities. Neither DPS officials nor McCraw answered the lawmaker’s questions, Canales’ staff told the Texas Observer.

2014

Operation Strong Safety II

Description: Perry deployed 1,000 Texas National Guard members and hundreds of DPS troopers to the border in June to assist law enforcement in decreasing drug and human smuggling in the Rio Grande Valley.

Stated reason: The governor and DPS cited a growing number of Central American children coming across the southern border, many of them through Texas, beginning in 2013. They said the rapid increase directly benefited Mexican cartels, which profited from smuggling fees and exploited the fact that Border Patrol agents were diverted from their regular duties. Perry, who was considering another run for president, blamed President Barack Obama for the influx. “I don’t believe he particularly cares whether or not the border of the United States is secure. And that’s the reason there’s been this lack of effort, this lack of focus, this lack of resources,” Perry said in a July 2014 interview with ABC News.

End date: Unclear. It morphed into Operation Secure Texas after Sept. 1, 2016, according to the Legislative Budget Board.

Cost: The estimated weekly cost was $1.3 million. It’s not clear how much was ultimately spent on the operation, but between 2014 and 2015, the Legislative Budget Board reported that the state spent about $124 million on Strong Safety II.

Claimed success: Perry boasted repeatedly about the initiative, saying Border Patrol apprehensions dropped as a result of the state’s operation. He did not explain how the state’s efforts led to decreases in federal apprehensions. In a report to the Legislature in February 2015, DPS also took credit, citing a decrease from 6,000 Border Patrol apprehensions in the first week of the operation to fewer than 2,000 after three months.

Reported concerns: While DPS touted seizing 150 tons of illegal drugs in six months, data obtained by the Austin American-Statesman showed the agency contributed to less than 10% of the operation’s drug seizures, with the rest coming from other law enforcement agencies, particularly the Border Patrol. Separately, Adam Isacson, a policy analyst at the Washington Office on Latin America, told FactCheck.org that Operation Strong Safety’s role was “minimal at best,” and a report by his organization argued that a combination of the federal government sending more Border Patrol agents and a crackdown by Mexico on immigration from Central America likely contributed most to the drop in apprehensions.

2015

Operation Secure Texas

Description: The initiative included 250 additional DPS troopers permanently stationed in the border region, plus a company of Texas Rangers. It also funded aircraft, boats and vehicles, as well as surveillance cameras and a training facility to address “cross-border corruption and other criminal activity,” Abbott wrote in a letter to then-Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson in September, the month the operation launched.

Stated reason: The initiative was a continuation of Operation Strong Safety, a multi-agency effort to “deny Mexican cartels and their associates unfettered entry into Texas, and their ability to commit border-related crimes, as well as reduce the power of these organizations,” according to DPS Director Steven McCraw.

End date: A Texas Monthly article said that the operation ended in 2018, but records obtained by ProPublica, The Tribune and The Marshall Project included a 2019 grant application to the governor’s office from Kleberg County that mentions additional workload under the operation as one of the reasons that the county wanted a prosecutor dedicated to border crimes.

Cost: In the letter to Johnson, Abbott said the bulk of the $800 million appropriated for border security in fiscal years 2016 and 2017 was dedicated to the operation. He did not give specific numbers.

Claimed success: DPS troopers assigned to the operation captured 7,508 pounds of marijuana, made 561 criminal arrests and issued more than 17,000 traffic citations from September through December 2015, according to presentations by the agency to the Texas Public Safety Commission.

Reported concerns: Lawmakers questioned the results of the operation during a public meeting of the Texas House Committee of Homeland Security and Public Safety in September 2016. “Are we actually more secure simply because we’ve done those things, and is there a number that will show us that in 2014 we were less secure?” asked former state Rep. Alfonso “Poncho” Nevárez, a Democrat from Eagle Pass. News reports from the time do not say if McCraw responded to the question.

2021

Operation Lone Star

Description: Under the operation that launched in March 2021, Abbott deployed more than 10,000 Texas National Guard members and DPS troopers to the border to combat drug smuggling and unauthorized immigration. For the first time, some immigrants are being arrested on state criminal trespassing charges after crossing into the U.S. on private property. The National Guard is also helping build border barriers and creating what Abbott and DPS call a “steel curtain,” a combination of vehicles, concertina wire and shipping containers, to deter anyone seeking to cross.

Stated reason: About two months after Biden’s inauguration, Abbott blamed the new administration for what he called an escalating crisis at the border. When the governor launched the operation, the number of people crossing into the state via the southern border had reached a two-decade high. Under Title 42, more than three-quarters of immigrants apprehended from January through March were immediately turned away.

End date: Ongoing

Cost: DPS estimates spending about $2.5 million per week for up to 1,600 troopers involved in the mission. The Texas Military Department estimates that the current deployment of 10,000 National Guard members will cost an additional $2 billion a year, nearly five times what the Legislature had budgeted for the deployment. The cost doesn’t include additional funding for related expenses such as jails, public defenders and grants awarded to local governments through the governor’s office.

Claimed success: State officials have touted more than 13,000 criminal arrests, tens of thousands of pounds of drugs seized and more than 230,000 unauthorized immigrants referred to the Border Patrol.

Reported concerns: An investigation by ProPublica, The Texas Tribune and The Marshall Project found that the state’s claims of success have been based on shifting metrics that included taking credit for uncovering crimes that had no links to the border, work conducted by troopers who were in the region before the operation began, and arrests, drug seizures and immigrant apprehensions made in conjunction with other agencies. More than nine months into the operation, DPS told the news organizations that it had removed about 2,000 charges it deemed not related to border crime from a dataset of arrests credited to Operation Lone Star. The state faces several lawsuits and calls for investigation from Democrats, lawyers and advocacy groups following media reports detailing alleged civil rights violations and court rulings raising questions about the constitutionality of the trespassing arrests. Despite DPS and Abbott’s office highlighting human trafficking and smuggling arrests, the largest share of arrests are of people accused of trespassing on private property. The Army Times and the Tribune have also reported about poor working conditions and suicides among National Guard members deployed under the operation.