This story is a collaboration between ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune.

The U.S. Department of Education has opened a civil rights investigation into a tiny Illinois school district for students with disabilities to determine whether children enrolled there have been denied an appropriate education because of the “practice of referring students to law enforcement for misbehaviors.”

The investigation was initiated Feb. 13, two months after ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune reported how the district, which operates a therapeutic day school for students with severe emotional and behavioral disabilities, turned to police to arrest students with stunning frequency.

An Education Department spokesperson said its Office for Civil Rights does not discuss details of open investigations. But in a five-page letter dated Feb. 24, federal investigators requested numerous records from the Four Rivers Special Education District, including details of every student discipline incident for the past two school years at Garrison School in Jacksonville.

For each incident in which police were summoned, investigators asked for the reason police got involved, an accounting of how much classroom time was missed and how that time was made up, and records of any communication with parents.

The district, which also provides special education services to students in nearby school districts, was given 15 days to respond and was directed not to destroy any records.

“I emphasize that at this time OCR has reached no conclusion as to whether the District has violated any law OCR enforces,” wrote Catherine Lhamon, assistant secretary for civil rights at the Education Department, in opening the case. Results of the department’s review “will have a direct and positive impact on students” at Four Rivers, she wrote.

In recent years, Garrison administrators called the police to report student misbehavior every other school day on average, the Tribune and ProPublica found. Staff members routinely asked to press charges against the children — some as young as 9 — and officers arrested them.

No other school district — not just in Illinois, but in the entire country — had a higher student arrest rate than Four Rivers, according to the most recent federal data that has been made public. That school year, 2017-18, half of all Garrison students were arrested. The school has fewer than 65 students in most years.

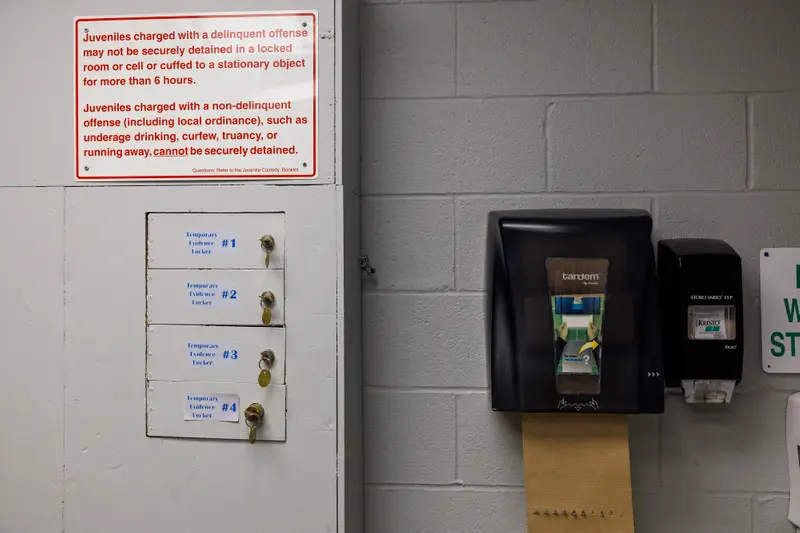

The Tribune-ProPublica investigation found that Garrison students had been arrested at least 100 times in the past five school years, including five students in the first 12 weeks of this school year. Officers typically handcuffed students and took them to the Jacksonville police station, where they were fingerprinted, photographed and placed in a holding cell.

There have been no student arrests since Nov. 15, when school administrators called police on a student who had spit at staff members. He was arrested for aggravated battery, records show. The next day, reporters visited the school for a board meeting and asked questions about Garrison’s approach to discipline, including its reliance on police. School officials said they had begun to make changes.

“I think it’s long overdue,” a parent named Lena said of the federal attention on Garrison. “I want some kind of change for that school and the students still in there. I want them to find out everything that was done; I want somebody held accountable for all the crap that people are put through there.”

One of Lena’s sons attended Garrison until September, when he was arrested at school and his parents decided to withdraw him. Her stepson was a student there in 2019 until she had him transferred to a private school. (When including the last name of a parent would identify the student — and in doing so create a publicly available record of the student’s arrest — ProPublica and the Tribune are referring to the parent by first name only.)

Although the civil rights office often launches investigations in response to a complaint, the Education Department said it initiated the Garrison case on its own.

“Probably from the media attention,” Four Rivers Director Tracey Fair told district board members at a meeting in late February when she briefed them on the investigation. A recording of the meeting was provided to ProPublica and the Tribune by Jacksonville news radio station WLDS.

Fair, who has overseen Four Rivers since July 2020, did not respond to reporters’ requests for comment. But she told the Tribune and ProPublica previously that administrators call police only when students are being physically aggressive or in response to “ongoing” misbehavior.

Records obtained by the news organizations, including 415 of the “police incident reports” that employees fill out every time they involve law enforcement, detailed instances when staff called police for a range of misbehavior, from disobedience to damaging a filing cabinet to shoving staff members. About half of the calls to police were for students who had run away from school, but those incidents rarely led to an arrest.

The school called police on a 12-year-old who was “running the halls, cussing staff” and on a student who broke a desk in the hallway after he was told he couldn’t use the restroom and left the classroom anyway, school records showed. Both students were arrested.

Education Department investigators are focused on whether school workers discipline students for behavior related to their disability — something explicitly prohibited by federal law — and fail to educate and support those students, according to the letter notifying Fair of the inquiry.

Investigators also asked for records detailing the reasons that students were transferred to

Garrison. Students, some of whom have autism, ADHD or other disorders in addition to their other disabilities, are supposed to stay at Garrison only long enough to get the skills and education they need to succeed, then transfer back to their home schools.

Concern about the students at Garrison has also prompted a separate inquiry by Equip for Equality, the federally appointed watchdog for people with disabilities in Illinois. In February, an attorney for the group sought the names and contact information of parents or guardians of Garrison School students, citing “probable cause to suspect educational neglect, i.e. that students with disabilities enrolled at Garrison School have been harmed by the school.”

The Equip for Equality letter, citing ProPublica and Tribune reporting, noted that the school had no curriculum for teaching social and emotional skills even though students are placed there because of their emotional and behavioral disabilities. It also referenced incidents that former students had described to reporters, including a teenager who reported being placed in a seclusion room for misbehavior and another student being denied access to the restroom.

After Four Rivers provided parents’ contact information to Equip for Equality, the organization mailed letters and flyers to current Garrison School families inviting them to reach out to an attorney with the group.

“We want to be able to help families and help the students get what they are entitled to. And we want to listen to what parents’ needs are and what students’ needs are,” said Olga Pribyl, vice president of the special education clinic at Equip for Equality. “We want to help them get back what they lost for educational opportunities for their children.”

The group’s efforts are focused on current Garrison students, but Pribyl said she also hopes to hear from former students who may have been denied educational services.

There have been signs of change at the small school. The Garrison principal, Denise Waggener, plans to resign effective June 30, and the school is looking to hire another social worker and behavior management specialist, board members were told at their meeting last month. Waggener did not respond to a request for comment.

The school added an “on call” social worker in November to respond quickly to classrooms when students are upset or struggling with their behavior. In the past, a “crisis team” of four aides would respond and could remove the student from class, sometimes putting them in a seclusion space or physically restraining them. Amy Haarmann, who is serving as co-principal until June, told the board the new social worker approach could “help us become a little more therapeutic.”

She said the number of crisis situations has decreased and no students have been arrested since the social worker was put on call. Jacksonville police have issued three municipal citations to students since Nov. 15, two for fighting and one for disorderly conduct, Jacksonville Police Chief Adam Mefford said Tuesday. Police were not called to the school at all in February, he said.

Other efforts to make the school more therapeutic and less punitive are being funded in part by a $635,000 federal grant through the Illinois State Board of Education. The grant is meant to fund training for staff to help students with their behavioral and mental health needs and reduce the reliance on punitive discipline.

Following the reporting by the Tribune and ProPublica, a team from the state board of education visited the school one day in December but did not mandate any changes. They confirmed an overreliance on police and said they plan to send a representative to monthly meetings with school leadership to discuss ways to help support students. The agency also connected school officials with education experts from universities in the state.

Michelle Prather, whose daughter Destiny graduated from Garrison in 2021, said she’s glad investigators are looking at the school. She said she believes an overhaul is needed.

“They need to shut it down or get new workers,” she said, for the sake of students. “I don’t feel like they get fair treatment and they’re actually learning. The teachers are not doing what they need to do.”