This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Idaho Statesman. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

It’s no secret that Idaho’s school buildings have problems. The state’s superintendents, maintenance directors, teachers and students see the leaks, pack into crowded hallways and feel the extreme cold and heat throughout the year. But state officials don’t know the extent of the issues because the last full review of school buildings was completed in 1993.

The Idaho Statesman and ProPublica joined forces to explore the deteriorating conditions and the consequences for students and teachers. To identify patterns, we worked with communities to bring together data, documentation and visual evidence from across the state. We spoke to as many people as we could, and visited dozens of schools, to see what conditions were like on the ground.

Here’s what we did.

We surveyed all 115 superintendents in the state and heard from 91% of them. Our data team helped design a survey inviting them to identify significant challenges in their districts. We first showed it to a small group of district leaders, who helped us anticipate and address potential concerns. In May, the state’s association of school administrators shared the link with its members, and regional leaders encouraged them to fill out the survey. We followed up with our own introductions and sent reminders throughout the year.

Our goal was to hear from every public school district so we could analyze how widespread facilities issues were and identify which respondents faced the most serious problems. All but nine responded: Arbon Elementary, Bliss, Council, Culdesac, Mullan, Pleasant Valley, Teton County, Troy and Whitepine. (Prairie Elementary did not complete the survey but provided information in an email.)

The responses came in from May 26 through Dec. 8. Most were filled out by current superintendents or facilities directors, but 14 have since left their positions or changed districts. At least a dozen superintendents shared assessments performed for them by firms or contractors.

Every district said it had at least one problem that posed a significant challenge or required major repairs, and 78% said they had five or more. Twenty percent said they had 10 or more problems. These are the problems, along with the percentage of superintendents who said they had them:

- Heating – 68%

- Cooling – 67%

- Roof – 61%

- Accessibility for people with disabilities – 58%

- Security (locks on classroom doors, secure entrances, etc.) – 58%

- Bathrooms – 58%

- Windows – 55%

- Leaky plumbing, walls, windows or roof – 50%

- Structural issues like cracks in the walls or foundation – 41%

- Traffic safety (at street crossings, in parking lots or in drop-off areas) – 38%

- Electrical (lighting problems, power going out, tripping breakers, etc.) – 35%

- Asbestos – 31%

- Overcrowding or use of portable buildings for extra space – 28%

- Fire and emergency preparedness – 26%

- Outdated technology or equipment – 16%

- Inadequate Wi-Fi – 10%

- Drinking water – 10%

- Other – 9%

Only 4% of superintendents thought they would be able to address the issues in the next year, while 20% said they may be able to.

When asked what was preventing them from addressing facilities problems, 88% mentioned funding.

We also asked superintendents about how they would rate the physical conditions of their schools. Not all respondents rated every school in their district, but together they rated 677 schools and said 21% were in poor condition, 41% were in fair condition and 38% were in good condition. Thirty-five percent said at least one-fourth of their schools were in poor condition.

We heard from 233 students, parents, teachers and others. In April, we published a callout. We wanted to talk to those most likely to be affected by facilities issues, such as people with disabilities or those in the most rural and remote corners of the state — where communities may not come across our online publications.

Dozens of Facebook and Reddit moderators supported our efforts to reach groups of educators, parents or residents in certain parts of Idaho. We spoke about our efforts at a meeting of the state’s special education advisory panel and handed out flyers at a conference for school administrators. The Idaho Education Association shared our callout with 10,000 members and asked for 200 flyers to put up in schools. Students and recent graduates told their friends about the callout while the Idaho Business for Education and the American Institute of Architects Idaho sent it to their members. Some local media outlets also helped spread the word, including Ben Reed with 99.1 La Perrona, who shared the Spanish translation of our callout.

Teachers helped us hear from students. Moscow High School English teacher Rachel Lyon shared essays from her students. Ninth grade student Natasha Gartstein wrote, “The Moscow High School has been in use for nearly 90 years. That’s before the Kardashians, Michael Jackson, and even the Beatles.”

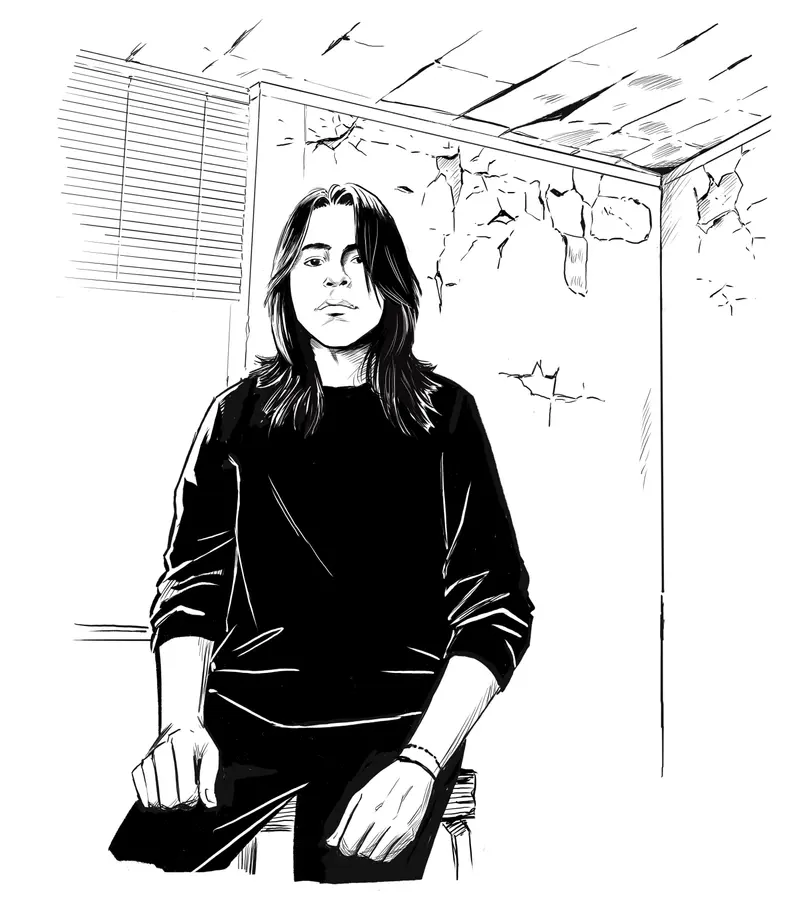

We also worked with artist Pia Guerra to draw illustrations of five students, two educators and a parent to help bring their stories to life.

We were given tours of 39 schools from maintenance directors, superintendents or principals. Maintenance staff were able to show us the problems going on behind the walls, which students and educators sometimes couldn’t see, along with the patches they’d used because they couldn’t afford a permanent fix.

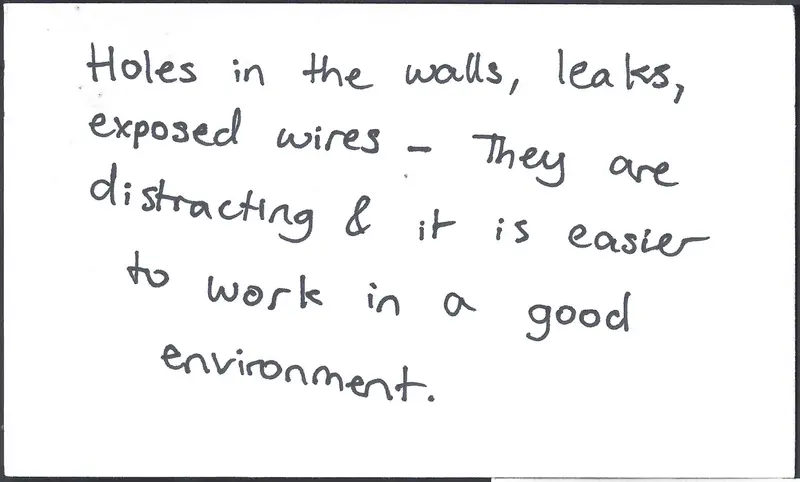

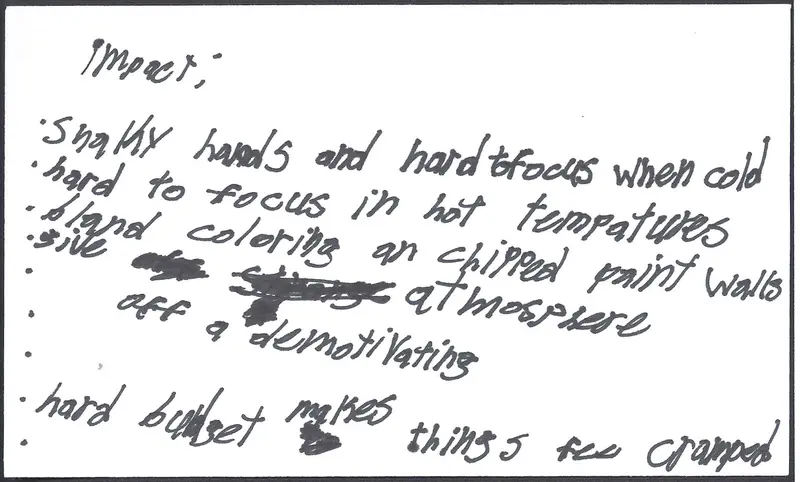

During our school visits, we met with students and educators. At six of these schools, we spoke to classes and met with the student government or student media groups. We explained our project and passed out notecards for students to write what they liked about their buildings, what they would change and the impact issues had on them. They often said they appreciated their teachers, who made do with the state of their buildings, and were proud to go to the same schools as their parents and grandparents. But we overwhelmingly heard about facilities problems. It was clear that students were aware of how school funding worked, with some explaining recent bond elections in their community.

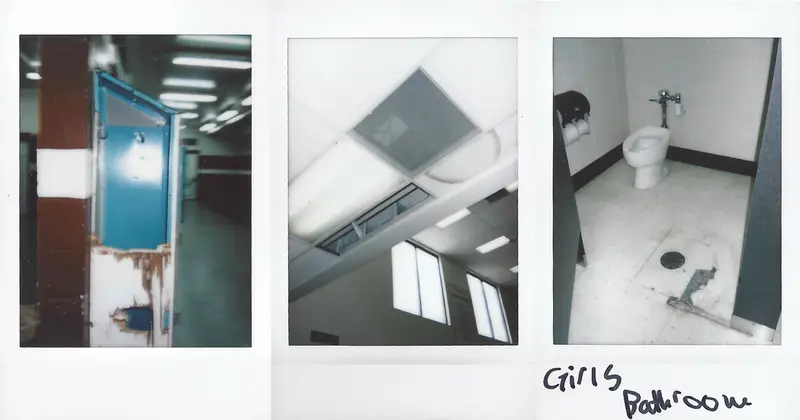

In some districts, we brought a camera that produces instant prints so students could show us the issues in their school buildings from their own perspectives. We received dozens of photographs back.

We verified the information. Before publishing, we reached out to the people who shared information with us to collect more details. We checked those accounts with the district to hear their responses and any updates on the conditions.

Nearly every example that made it into our story was something that the districts agreed was an issue. In a few cases where the district disagreed with parts of a student or community member’s account, we noted that in the story.

If you’d like to get in touch with our team, you can email [email protected]. If you’re an educator who might be interested in using our project in your classroom, we’re happy to assist however we can. If you’re interested in classroom materials or updates about this project, send us an email.

If you want to talk to us about schools in another location, you can use our general tip line at propublica.org/tips. We can’t guarantee that we’ll be able to follow up on everything, but we review everything we receive.