This article was produced in partnership with Searchlight New Mexico, which was a member of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network. Sign up for Dispatches and Searchlight’s free newsletter to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Last year, 63 kids in New Mexico turned 18 and aged out of foster care. It’s a fraught time; after spending their lives in a system that micromanages their every move, the teens are thrust into adulthood, left to fend for themselves while struggling with the aftereffects of a childhood often spent cycling among foster homes. Some thrive. Many do not.

Roughly 30% of foster youth end up homeless after aging out of foster care, national studies show. An estimated 1 in 4 end up incarcerated.

The New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department has made efforts to reverse those grim statistics. Notably, CYFD launched its Fostering Connections program in 2020 for youth who age out of the foster system. It offers some assistance with housing, food and behavioral health care.

That’s often not enough, advocates say. Children in foster care experience high levels of trauma and high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health conditions. Adding to their struggles, CYFD has been housing foster children in inappropriate and sometimes unsafe settings, where they can’t get the stability and psychiatric care they need. A 2022 investigation by Searchlight New Mexico and ProPublica found that some of CYFD’s highest-needs kids spent years going back and forth between psychiatric hospitals and youth homeless shelters. (CYFD leadership has previously acknowledged that kids should not be staying in shelters, but that sometimes they “have to make very difficult decisions under extraordinary circumstances.”)

Finding a place to live, getting work, buying a car and navigating the world can be overwhelming for any teen — but it’s even more so for teens who haven’t had supportive families and don’t have an adult in their life who can help.

Even teens who sign up for Fostering Connections can fall through the cracks. It can take months before they start receiving aid through the program, leaving them in limbo at one of the most vulnerable periods of their lives. According to their attorneys, teens can be so traumatized by their time in foster care that they refuse any offer of assistance from the agency after they’ve aged out. They’re determined to leave the state’s orbit completely.

Here are the stories of two young women who aged out last year. Although their stories are different in many ways, one difference in particular stands out: In the months after leaving foster care, one had the consistent support of a caring adult. The other didn’t.

Birdie

Roberta Gonzales, who goes by Birdie, was 10 years old when she and her younger brother were taken out of their aunt’s home in Albuquerque and placed in foster care. Her brother was adopted; Gonzales has not seen him since. But CYFD never found her a stable home.

Instead, she spent the rest of her childhood in residential treatment centers, first in San Marcos, Texas, and then at Desert Hills, one of several mental health facilities in New Mexico that have shut down in the last five years amid allegations of abuse, lawsuits and pressure from state regulators.

By 2019, with fewer residential treatment centers at its disposal, CYFD was increasingly relying on youth homeless shelters to house high-risk kids, including some who were suicidal. Once there, many teens routinely experienced mental health crises or ran away. When no shelters were available, CYFD would house some of them in its Albuquerque office building.

Gonzales was one of these teens. The cots and bean bag chairs at the CYFD office were too uncomfortable to sleep on, she recalled. “I usually just slept on the floor.”

Gonzales turned 18 last year and, after a stint in Las Cruces, moved back to Albuquerque.

One of her favorite things to do was attend services at places like Calvary Church, which hosts community events like an annual Fourth of July fireworks show, or Sagebrush Church, both in Albuquerque. She said she liked the pastors and the music.

As a former foster youth, Gonzales was entitled to housing assistance from CYFD. The agency helped her start the paperwork when she was 17, but as her 18th birthday came and went, she was unclear how the system worked and still had no idea what help she would get or when. Her former caseworker called to check on her periodically, she said. But she never seemed to get the help she needed.

“I got kicked out [of foster care] on my birthday and now I’m homeless,” she said. “CYFD just left me to do this on my own.”

When asked for comment, a CYFD spokesperson said that “Fostering Connections benefits are generally seamless.” It might take time for some youth to receive benefits after they turn 18, but “CYFD staff does assist with the paperwork and resources,” the spokesperson said.

After Gonzales aged out, an uncle gave her a little money to pay for food, clothes and shelter. The money went fast. Within weeks, she was broke. She lived briefly with a cousin before moving into a Christian adult homeless shelter.

But she found the shelter’s tight quarters and strict rules too stifling and soon decided to leave. She spent much of her time at the Alvarado Transportation Center bus stop downtown, sometimes riding the bus around town to pass the time.

For a brief period, Gonzales’ uncle paid for a room in a motel so she could have a safe place to sleep for a few nights. The room — complete with a clean bed, pillows and private bathroom — was like heaven, she said.

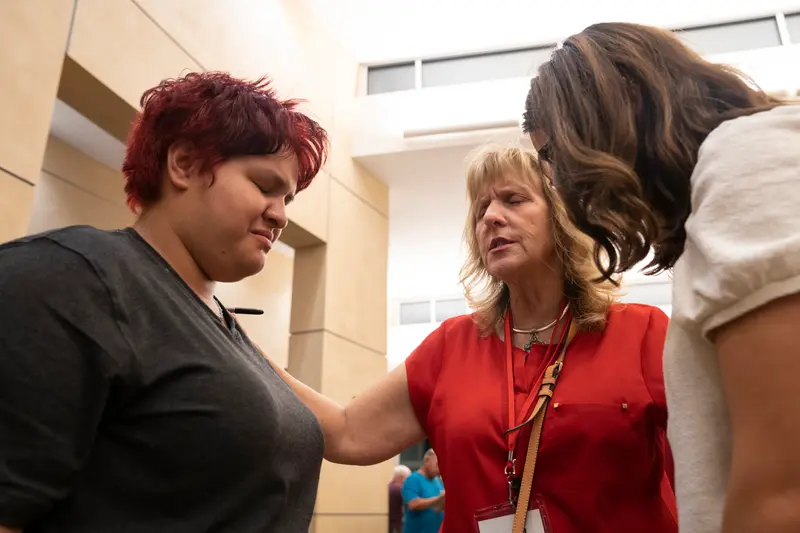

Later that week, Gonzales went to Calvary Church, where a volunteer offered to pray with her and another woman joined in. Gonzales had told pastors at both Calvary and Sagebrush churches that she was homeless and living on the street. One pastor prayed with her and signed her up for a baptism.

Before going to Calvary Church, Gonzales had met a group of people who offered to take her to the Savers thrift shop so she could get some new things to wear. Someone had stolen her belongings, so she was ecstatic about the shopping trip. She eagerly tried on her new clothes in the Calvary Church parking lot and carried the Savers bag with her for days, with all her possessions inside.

After trying on clothes, she had no plan for where to sleep or what to do for food — that night or in the days ahead. She looked for somewhere to sleep after midnight. She found a ledge in front of her favorite bus stop.

But when a security guard spotted her and told her to leave, she walked across the street and settled on the sidewalk.

The following afternoon, Gonzales started to have difficulty breathing and began to feel very hot. After she called 911, paramedics met her under an overpass.

She was taken to the University of New Mexico Hospital and wheeled to a room. “It feels like I’m dying,” she told doctors.

Gonzales had previously been to the UNM Hospital, for various issues, and some of the nurses knew her by name.

Being at the hospital wasn’t so bad, she said — it was a comfortable place to sleep for the night, and she could charge her phone.

“Any changes to your address?” doctors asked her while preparing a nebulizer to stabilize her breathing. “I have no address,” she replied.

She stayed at the hospital for several days while the staff monitored her lungs. Doctors later diagnosed her with Castleman disease, a rare disorder that affects the lymph nodes.

More than a year has passed since then. When contacted this fall, Gonzales said she’d reconnected with her mother and talks to her regularly. She said a CYFD Fostering Connections worker has been in touch with her and checks in periodically over the phone. Although CYFD provides job assistance for youth who age out, it hadn’t helped her find a job, she said, so “I’ve been looking myself.” The agency hadn’t helped her find housing either, she added. She did find a place to live, briefly. But it didn’t last.

“I’m homeless again,” she said in September. Until she can find stable housing and a job, she’s living at a homeless shelter in Albuquerque.

It doesn’t always happen this way. With the right support, youth can thrive after foster care.

Nevaeh

Nevaeh Sanchez was 15 when CYFD investigators determined she needed to be taken into foster care. She and her younger brother had been living with their father in a run-down house in Española that didn’t have running water.

When a caseworker arrived to pick her up, she and her brother were driven not to a foster home, but to a youth homeless shelter in Taos, where they lived alongside other kids with nowhere to go.

CYFD told Sanchez and her brother they would be in the shelter for just a few days while the state found them a relative to stay with, or until the agency’s investigation was complete and they could return home. But the days turned to weeks, and the weeks to months. “We didn’t even know we were in the [foster] system until two months in,” Sanchez said.

Three months after her arrival in Taos, shelter staff kicked her out after finding marijuana in her room. CYFD moved her to a homeless shelter in Santa Fe. Then the agency moved her to another shelter in Albuquerque, then to another. And another. Between shelter stays, she would sleep in CYFD’s Albuquerque office building.

“It’s all just a waiting game” until they can find you a bed, which was inevitably at a shelter, Sanchez said. Kids say this “shelter shuffle,” as it’s known, makes them feel like the system has given up on them.

Many of the teens Sanchez lived with in the shelters had nobody to support them and found themselves thrust into adulthood alone after aging out of foster care. But in this respect, Sanchez was lucky.

When she was taken into the system, a judge assigned Lori Woodcock to be her court-appointed special advocate, or CASA — a volunteer trained to support children in foster care.

CASAs have a critical role: They gather information about a child’s foster care case, recommend services and advocate for the child’s best interest in court proceedings. The help they’re allowed to provide, however, is mostly limited to issues related to the court case.

Sanchez needed help with real-world issues — finding a job, getting to work, finding a place to live.

“As a CASA I couldn’t drive her to appointments or job interviews, or any of the things she actually needed help with,” Woodcock said.

So Woodcock quit her role as a CASA volunteer, opting instead to work independently as a mentor to Sanchez. Working outside the foster care system, she was able to give Sanchez the help she needed to get on her feet.

The Fostering Connections program offers some services for teens when they turn 18 to ease the transition out of foster care. But Sanchez said she didn’t get any help at the time of her birthday.

Sanchez had spent nearly all her time in foster care living in the shelter system, where the staff monitored the children 24/7. She always shared a room with other kids and needed permission to use her phone, go for a walk or even close a door.

But when she turned 18, with the help of Woodcock, she found a rental with a room of her own.

“I’ve never had a chance to live” before now, she said. “I’ve been surviving.”

In May 2021, Sanchez applied for a job as a cashier at the Frontier, a popular restaurant across the street from the University of New Mexico campus. She held the job for two and a half years — even earning three raises for good performance.

“She’s thriving,” Woodcock said.

Another huge step was getting her own cellphone.

During her time in foster care, Sanchez’s phone use had been regimented. Most shelters prohibit phones entirely because of liabilities and safety protocols.

Last summer, she bought a phone with her own money.

But there was an even bigger milestone to tackle: getting a car. With a vehicle of her own, she wouldn’t need to rely on others to get to work or to appointments in a city as sprawling as Albuquerque.

She had already gotten her driver’s license. But Sanchez had no savings. It was nearly impossible to find a used car that she could afford.

Then Woodcock saw a 2001 Dodge Neon for sale. She purchased the car outright for Sanchez, who reimbursed her over the following months.

It was a momentous step.

She’s now paid back the entire cost of the car — $3,000.

“She’s my role model,” Sanchez said of Woodcock. “I’m very glad that that woman found potential in me and helps me with my life. She sets me up for the right path.”

“Having even one single caring adult in a young person’s life can absolutely mean the difference between success and failure after leaving foster care,” said Annie Rasquin, executive director of CASA First, the office where Woodcock worked before leaving to help Sanchez.

The gaps in the CASA system have always been a problem, Rasquin said. Inspired in part by the success of Woodcock’s work with Sanchez, CASA First established a mentorship program this year. It trains volunteers to give extra support to foster teens who need it.

In October, Sanchez started focusing on her GED full time. In the coming years, she said she hopes to start a business as a cosmetologist or tattoo artist. Her Fostering Connections worker has helped her in making plans for the future, she said.

In the past, “I had nothing — 100% no control over my life,” she said. “I’m finally getting up for the first time.”