In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which pushed for museums, universities and other organizations that possessed Native American human remains to return them to Indigenous communities. But our reporting shows that many institutions still hold many of those remains in their collections. Last month, ProPublica published a database that allows you to search the repatriation records of these hundreds of institutions.

But the full story of repatriation goes beyond the numbers, as illustrated by our story about a state museum in Illinois that was built on Native American burial mounds. This guide is for reporters who want to take a deeper dive on repatriation at institutions in their area.

- 1. Understand the Repatriation Process.

- 2. Dig Into the Data.

- 3. Gather Documents.

- 4. Talk to People With Experience.

1. Understand the Repatriation Process.

Key terms

- Human remains: The physical remains of a person of Native American ancestry. Each inventory record lists the minimum number of individuals (MNI) represented by the remains. We’ve avoided referring to Native American remains as “collections” or “sets of remains” in our reporting, though the terms are commonly used. Instead, to highlight the humanity of the individuals, we have opted for phrases like “remains of Native Americans” or “ancestral remains.”

- Associated funerary objects (AFO): Items found with human remains that are also in an institution’s possession. Also consider using “funerary belongings.”

- Inventory: Item-by-item descriptions of human remains and associated funerary objects. The institution that holds them provides this list to the federal government and potentially affiliated tribes.

- Cultural affiliation: A shared group identity connecting a present-day tribe with an earlier group. The standard for establishing affiliation is a preponderance of evidence.

- Preponderance of evidence: A legal burden of proof that is met when something is more likely than not.

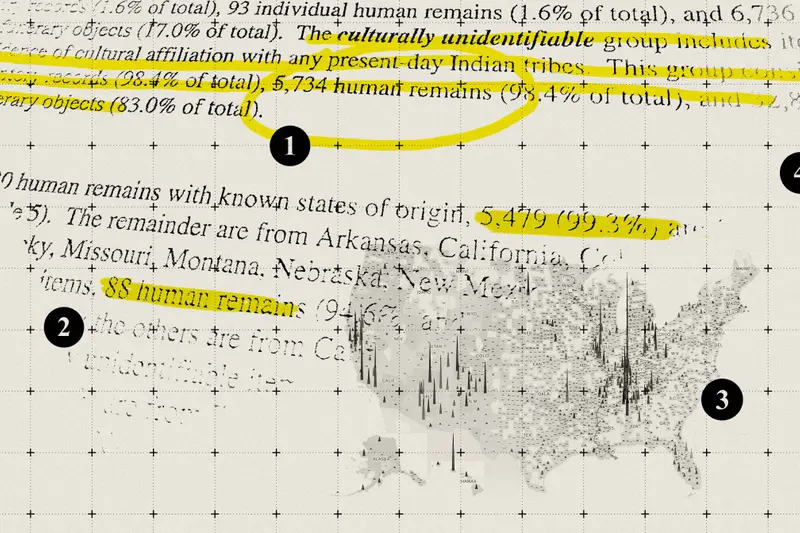

- Culturally unidentified: Remains and items for which no culturally affiliated tribe has been determined, according to the institution that holds them.

- Disposition: When culturally unidentified remains and associated funerary objects are transferred to tribal control through geographic affiliation instead of cultural affiliation.

- Notice of inventory completion: A notice published in the Federal Register when an institution determines that certain remains and funerary objects are culturally affiliated with one or more tribes, or will repatriate based on a geographical link.

More information is available on the NAGPRA site’s glossary page.

Read up on the law and regulations.

NAGPRA applies only to institutions that receive federal funds and have Native American human remains or cultural items. The law provides a process for consultation and repatriation.

The National NAGPRA Program, which operates under the Department of the Interior, helps administer the law. The program runs a website that provides useful resources on terminology; compliance; inventory records; the duties of the NAGPRA Review Committee, which monitors and reviews the implementation of the law; annual reports to Congress; enforcement; and more.

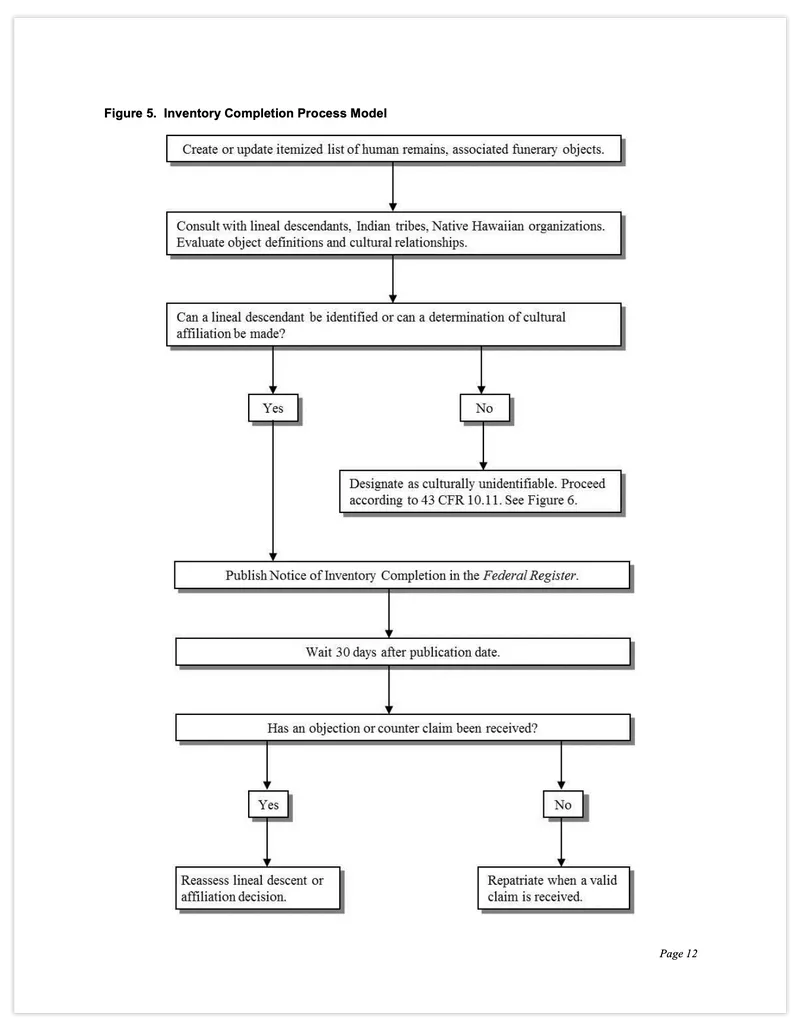

To understand the law’s goals and how it has been implemented, read the text of the act and the history of legislative intent. The Department of the Interior administers the law and has issued a series of regulations since 1990. Notably, in 2010 the department created a pathway for the return of remains and items whose cultural affiliation cannot be established. This year, the department is seeking to update the regulations to expedite the repatriation process.

To show what the law requires of institutions, the NAGPRA Community of Practice, a network of people who work on NAGPRA, created a flowchart and museum guide. The National Park Service also has an in-depth guide on NAGPRA compliance.

Repatriation can be requested by direct descendants, by federally recognized tribes and Alaska Native entities, or by Native Hawaiian organizations. Institutions are not required to consult with tribes that lack federal recognition. However, in some cases museums have chosen to consult directly with these tribes, or with a federally recognized tribe acting as an intermediary.

Institutions may repatriate Native American remains to multiple tribes. In these cases, the tribes often work together to determine what they’d like to do with the remains.

2. Dig Into the Data.

Search the ProPublica NAGPRA database.

Our tool adds visuals and a search function to a data set maintained by the National Park Service that itemizes all the Native American human remains and associated funerary objects that roughly 600 institutions have reported to the federal government. The data set includes information on the state and county that remains and objects were taken from, which institutions hold them and whether they have been made available for return.

You can type the name of an institution, tribe or state into the search box, or click on counties in the national map to learn more. All institutions, tribes and states are listed at the bottom of the page.

State and county pages: If you want to start exploring geographically, each state has a page (e.g., California) that lists the institutions in the state that hold remains or items from anywhere in the country. The page also lists what institutions hold remains and items that were originally taken from that state. It also shows the percentage of remains each institution has made available for return and to which tribes. From the state pages, or from the map on the main page, you can drill down to county pages (e.g., Apache County, Arizona), which show the status of human remains originally taken from that county.

Sometimes institutions make conflicting decisions about human remains and items taken from the same area. State and county pages make it easy to identify these disagreements. For example, federal agencies have been generally more likely than museums to repatriate remains taken from the Southwest area. Further reporting could explain why some institutions have kept remains and objects while others have returned them.

Institution pages: The institution pages (e.g., University of Arizona) provide a summary of where the ancestral remains in an institution’s inventory were taken from and which remains the institution has not made available for return.

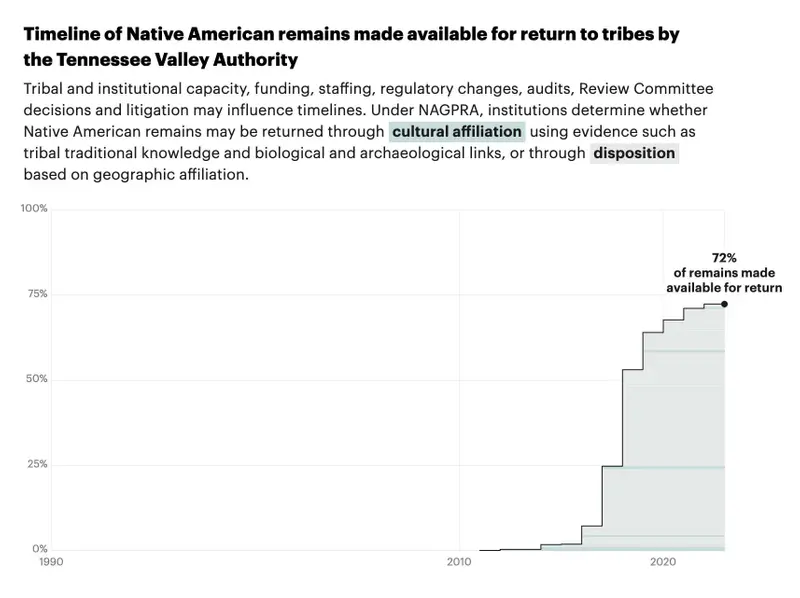

The timeline chart on these pages shows the institution’s progress since NAGPRA was passed and can identify important events in the institution’s history. For example, the Tennessee Valley Authority did not start making remains available for return until the 2010s. Since then, a majority of the Native American remains in its possession have been made available for return. What changed? A critical government audit sparked reform.

Keep in mind that some institutions, like Stanford University, completed repatriations prior to NAGPRA’s passage. The data ProPublica published only reflects what institutions have reported since the law came into effect. We have no way to consistently track repatriations before that.

Tribe pages: ProPublica for the first time made the NAGPRA data set searchable by tribe (e.g., Chickasaw Nation). The pages show where Native American remains that have been made available for return to a tribe were taken from and which institutions returned them. They also include a list of institutions that may have ancestral remains taken from counties of interest to each tribe. This information can help NAGPRA coordinators identify tribes that should potentially be contacted about unrepatriated remains. Keep in mind that institutions may make remains available for return to multiple tribes and that the remains listed on tribes’ pages are not necessarily exclusive to one tribe.

Request inventory record data from the National NAGPRA Program.

The National NAGPRA Program has additional detail on specific inventories broken down by institution, state or county. This information can help reporters understand how remains were acquired and make comparisons between institutions. The level of detail that institutions provide varies. Due to concerns about looting, we decided not to publish specific information about the sites that remains were taken from, unless the site is already commonly known, like a national monument or state park.

Caveat and contextualize the data.

The data is self-reported by institutions. Institutions give a minimum estimate of how many Native Americans’ remains they hold, and they frequently adjust these numbers. Some institutions subject to NAGPRA have failed to report the remains in their possession. As a result, the numbers are best taken as low-end estimates.

The data can appear deceptively precise. When speaking generally about what an institution has, we recommend rounding numbers to the nearest tens or hundreds. For example, “The University of California, Berkeley reported still having the remains of at least 9,000 Native Americans” instead of 9,075.

Some institutions claim that all of the human remains subject to NAGPRA in their holdings are “available for return.” What they mean is that everything has the potential to be returned, pending a tribal claim, consultation, determination by the institution and publication of a notice detailing the list of tribes eligible to claim the remains. We use “made available for return” only for remains that have already been through that process, and the only step left is for the specified tribes to decide what they’ll do with the remains.

The physical transfer of remains can take time. Tribes might not have the money, space or capacity to complete this last step. Also, tribes sometimes establish agreements under which remains stay in the care of museums but legal control of them is transferred to the tribes.

That said, many of the remains described as “made available for return” have been physically returned. We’d like to say when physical return occurs, but the federal government doesn’t collect that data. If you contact an institution individually, it may share this information.

3. Gather Documents.

Search the Federal Register for notices.

When an institution establishes a connection between tribes and remains, it must publish a list of the tribes eligible to make a repatriation claim. These notices are published in the Federal Register and are searchable. Try searching for “Notice of Inventory Completion,” followed by the name of the institution or tribe you’re interested in.

Tribes and institutions sometimes change their names, so the present-day name may not exactly match what’s listed in the notice.

Notices describe the Native American remains and associated funerary objects being made available for return. They contain information on which tribes were consulted, how the remains came to be in the institution’s possession, and who to contact at the institution. Occasionally, the evidence used to determine a cultural affiliation or disposition of the remains is also included.

Request records.

Other documents can aid in reporting on NAGPRA. Look for records that:

- Detail how the institution acquired the Native American remains and items reported in its inventory (also known as their provenance).

- Explain the behind-the-scenes decision-making on whether to repatriate and the evidence used.

- Show the quality of relations between the institution and tribes.

Records you can seek include:

- Original inventories or summaries of Native American remains and cultural items that institutions send to tribes. Copies are sent to the National NAGPRA Program.

- Excavation field notes. Many remains were removed in federally funded excavation projects or by academically oriented field schools in the 20th century, and both of those endeavors often produced significant archives.

- Loan files that document requests and transfers of Native American remains and objects between institutions, potentially for research purposes.

- Notes or internal email correspondence from NAGPRA staff, faculty, administrators, legal counsel, tribes or colleagues at other institutions.

- Materials and notes used during consultations. Institutions often prepare materials for their meetings with tribes and take notes.

- Recordings of consultations. During the pandemic, many meetings were held over Zoom and may have been recorded.

- Tribal claim documents. These may contain information that tribes do not want shared publicly because they are culturally sensitive or could aid looters.

- Determination records. These may explain the rationale behind determinations of cultural affiliation or disposition.

- NAGPRA Review Committee transcripts. Disputes are often brought before committee, and you can search for mentions of tribes, institutions or regions.

- Grant application materials. When institutions apply for NAGPRA or other government-funded grants, the application materials and statements supplied may provide insight into their budgets and intent. You can request these records from the agency that administers the grants.

- Historical documents, such as field notes and annual reports, that may not be online.

- Appraisal documents for objects.

Note that while freedom of information laws make it possible to request records from public institutions, private institutions’ records are much harder to obtain. In those cases, you may have luck by requesting records from amenable institutions or groups that have corresponded with or worked on consultations with them.

4. Talk to People With Experience.

The history of the taking and repatriation of Native American remains and cultural items varies by region. Familiarize yourself with the history of Indigenous peoples and institutions in your area. Talk to tribal and institutional representatives to understand how efforts to repatriate have proceeded since NAGPRA’s passage in 1990. There may have been several rounds of consultation between tribes and institutions. And when repatriation efforts stretch back 30-plus years, it may help your reporting to piece together a chronology of who represented each group.

Talk to representatives of tribal nations.

Learn the basics of repatriation before approaching sources. Be prepared to explain why you’re interested in reporting on this topic. Look up the tribe’s page on ProPublica’s NAGPRA database as a starting point to understand which institutions they may have consulted with already.

Tribes generally have designated NAGPRA specialists. Often, they are a tribal historic preservation officer or cultural director. Use these directories to find a point of contact:

- National NAGPRA Program Contacts Database

- National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers directory

- Tribal Leaders Directory: Department of the Interior

- Native Hawaiian Organization List: Department of the Interior

Reach out to tribal reps early, since they can be very busy. Know that tribes have different views on how best to repatriate. Tribes are not always ready to repatriate and don’t always want remains to be physically returned. Sometimes multiple tribes make competing claims that take time to sort out. Tribes may be open to respectfully conducted research.

Also, keep in mind that tribal leaders may not want to discuss repatriation and might not see news coverage as beneficial, especially if they’re in the middle of consulting with institutions and need to maintain those relationships. Repatriation can be a private issue in some cultures, and some do not have a cultural protocol for handing the dead.

Ask about successes and challenges the tribe has faced in their repatriation work. Have tribes had sufficient funding to pursue consultation and repatriation? What has been positive or negative about their experiences? Have institutions been proactive in reaching out to them and sharing information about ancestral remains and cultural objects in their collections?

It’s critical that both tribes and institutions have sufficient funding to work on consultations and repatriations. Many tribes and institutions don’t have a dedicated, paid staff member to work on NAGPRA issues, and even when that role exists, turnover can be high. Stable funding allows for long-term relationship-building between tribes and museums who often must engage with each other over years to complete the process.

Talk to museum representatives.

The number of people involved in NAGPRA work varies by institution. Some institutions have full-time NAGPRA coordinators, while others rely on individuals who have other responsibilities, often as professors or curators.

Some institutions list a NAGPRA contact on their websites. Otherwise, you can find out who to talk to by looking at the National NAGPRA contacts database. If the institution has published a notice in the Federal Register, those often include contact information, and you can find them with a “Notice of Inventory Completion” search as explained above.

Some questions we suggest asking:

- Is the data maintained by the National NAGPRA Program accurate? If the institution says the data is out of date or inaccurate, ask it to elaborate on specifically what is incorrect and to update its federal records.

- What efforts have been made to consult with tribes on remains that have yet to be repatriated? When did the museum last reach out to tribes? Some institutions say they have followed the law because they invited tribes to consult when the law was first passed and they didn’t get a response. That approach doesn’t match the spirit of the law. Some tribes have several dozen institutions holding human remains and objects that could potentially be repatriated to them, creating a burdensome workload for tribes.

- How were decisions about whether to repatriate made? Who have been the decision-makers?

- If an institution has not repatriated remains taken from a specific region or site, while others have, get in touch with the ones that did repatriate and ask why their determinations were different.

- How does the institution fund NAGPRA work? How many staff positions are dedicated to it?

- What is the institution’s policy on research, teaching, display, imaging and circulation of human remains and cultural items that are potentially subject to NAGPRA? NAGPRA does not prohibit these practices, but tribes often find them to be disrespectful.

Lastly, keep in mind that even if a museum is not listed in the database, it might have unreported Native American remains that are subject to NAGPRA. Small or private institutions that have received federal funding might not understand that they are subject to the law. In a 2021 article, Indian Country Today looked into whether institutions that had accepted stimulus funds may be subject to NAGPRA.

Talk to people involved with repatriation.

People have been working on repatriation for a long time, and it’s important to understand the variety of opinions on how to approach the issue. Perspectives on NAGPRA have been shared in academic publications dealing with fields such as law, museum and heritage studies, Native American studies, anthropology and archaeology.

The NAGPRA Community of Practice is a network dedicated to supporting the implementation of the law. The group offers training resources and holds meetings twice a month.

The NAGPRA Review Committee’s members are nominated by tribes and national museums or scientific organizations.

The National NAGPRA Program can be reached at [email protected].

Get in touch with us.

If you publish a story about repatriation using our data, let us know! You can contact our reporting team to share stories or ask questions at [email protected].

We have also solicited tips about repatriation from readers across the country. With the permission of those who wrote in, we may share tips with local newsrooms. If you are interested in being part of this effort, let us know by emailing us with the subject line “Interested in Tips.”